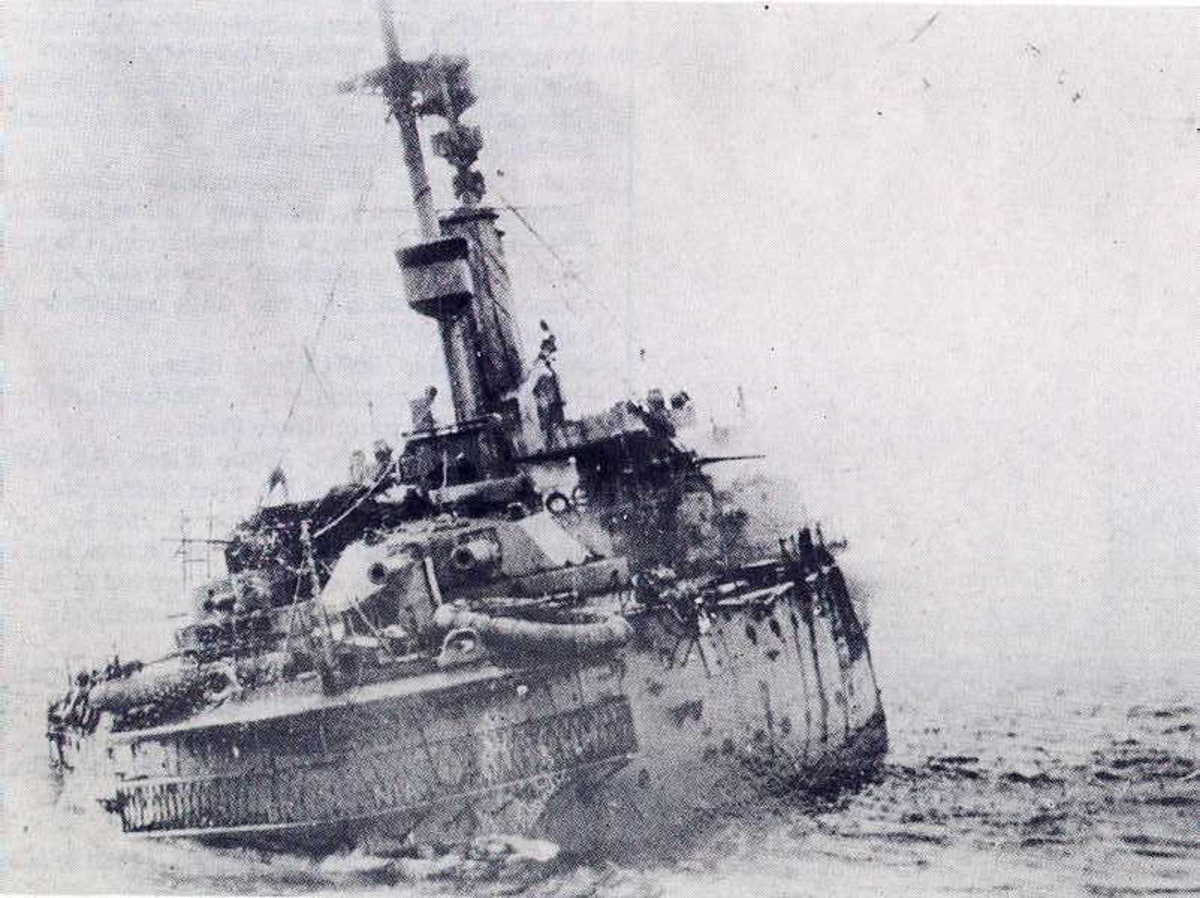

HMS Victoria was the lead ship in her class of two battleships of the Royal Navy.On 22 June 1893, she collided with HMS Camperdown near Tripoli, Lebanon, during manoeuvres and quickly sank, killing 358 crew members, including the commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet, Vice-Admiral Sir George Tryon. One of the survivors was executive officer John Jellicoe, later commander-in-chief of the. Green Crack is the lovechild of an Afghani strain crossed with Skunk #1, and it smells and tastes like sweet fruit with some hints of tanginess and flowers. Those who are interested in growing Green Crack seeds are advised to do so outdoors as the plant thrives best there. Officially, a total of 1,554 ships were sunk due to war conditions, including 733 ships of over 1,000 gross tons. Hundreds of other ships were damaged by torpedoes, shelling, bombs, kamikazes, mines, etc. Foreign flag ships, especially those with Naval Armed Guard on board as well as ships belonging to U.S. Territories such as the Philippines.

Introduction

The British Navy as it appears at the battles of the Nile and Copenhagen cannot be properly understood without considering the preceding eight years of war with Revolutionary France, the semi-disaster at Toulon, against the young artilleryman, Bonaparte, the (real) fear of invasion, the growth of the empire, the huge efforts at recruitment into navy, the advances in port technology, the increasing number of enemy ships captured and the weakness of the France, Britain’s principal rival. In fact the secret of the success of the navy lay in two key areas: huge investment, both in money and manpower, irreplaceable experience in sea fighting.

The fleets of Europe in 1792 (selection)

Britain

Total vessels Total cannon Total crew

661 14,000 100,000

France

Total vessels Total cannon Total crew

291 12,000 78,000

Spain

Total vessels Total cannon Total crew

222 10,000 50,000

Russia

Total vessels Total cannon Total crew

803 9,000 21,000

Holland

Total vessels Total cannon Total crew

187 2,300 15,000

These statistics come from civil engineer Robert Fulton’s book Torpedo War, and submarine explosions, New York: W. Elliot, 1810

Investment

Toy Royal Battleship

The British seizure of French colonies 1795, notably, Tobago, Santa-Lucia and Martinique, including influence over Saint-Domingue (and finally the taking of Trinidad in 1797) meant that British trade flourished – for example, 14,334 merchant vessels with 1.437m tonnes of goods in 1792 grew to 16,552 vessels carrying 1.797m tonnes in 1802. In short, enough to pay for the largest fleet in the world. Furthermore, these British gains were French losses.

Recruitment

With the beginning of the war with Revolutionary France in 1793, parliament decreed that the manpower in the Royal Navy should increase to 45,000 (the population of England before the first census of 1801 was estimated at 8.6 million). The total number of men required for the fleets in 1794 rose to 85,000 in 1794 and 120,000 in 1799, of which there were 106 admirals, 515 post-captains, 394 commanders and 2,091 lieutenants. Three methods were used in the attempt to meet these quotas: volunteers: the pressgang and (post-1795) the Quota Acts.

Volunteers

A man who entered the navy as a volunteer was given his shilling and two months pay in advance (using which he was supposed to provide himself with a hammock and some clothes). Becoming a sailor was also a way of avoiding debtors’ prison, since the Navy protected a man from his creditors provided that the debt was less than twenty pounds. On the other hand, it was not always clear whether a volunteer had not in fact been pressganged – often men captured by the pressgangs were given the chance to volunteer and thus receive their pay. Volunteers were much appreciated and usually made the best crewmen, as the expression ran ‘Better one volunteer than three pressed men’.

The Impress Service or pressgang

Founded long before the Napoleonic wars, the Impress service came into high profile during the wars with Revolutionary France. The word impress was derived from the old French word ‘prest’, modern ‘prêt’ or loan/advance, in other words, each man ‘impressed’ received the loan of a ‘shilling’ (that is he paid the ‘King’s shilling’ to enlist) and became a ‘(im)prest man’. The service was present in every major port in the kingdom. The service’s offices were called ‘Rendezvous’ with a Regulating Officer in charge, and he hired local hard men as ‘gangers’. These thugs would thus roam the countryside attempting to ‘encourage’ men aged between 18 and 55 to join the navy. No-one was safe from the gang, and often the only escape route when captured was to bribe the gang or to join it. A preferred target for the pressgang was the merchant navy, so it was not infrequent to find special hiding places on merchant vessels. Also, the return of prisoners of war from France was also seen as the perfect moment to impress crewmen, such that very often the returning POWs were turned round and pressganged even before they set foot once more on home soil. The captains of merchant vessels frequently took pity on those they were repatriating and tried to let them land in places far from the ports and the pressgangs.

Quota men

In 1795, prime minister William Pitt the Younger passed two bills through parliament, called the Quota acts. In conformity with these acts, every county was required to supply to the navy a quota of men, in proportion to the country population and the number of ports – for example, London was asked to provide 5,700 men, whilst Yorkshire, the largest county, was obliged to offer 1,081 hommes. Depite promises of rewards, very few county men came forward. As a result, small time criminals were given the choice of a prison sentence or service in the Navy. Given the exceedingly rough justice prevalent in 18th-century prisons, many preferred the call of the sea. One unfortunate result however of this policy was that the criminals brought with them typhus, also known as Gaol fever, onto previously healthy ships!

Royal Battleships Cracked

Modern dockyards for a growing navy

British naval dockyards were the subject of investment throughout the five year period 1796-1801. Most notably, the docks in Portsmouth were refitted – new wet and dry docks were excavated, and the docks themselves were drained using steam engines. These developments, because they speeded up the turn around time for ships in the docks, put an end to the problem of excessive number of ships requiring refitting. Furthermore, the British sailors were renowned for their ability to perform repair work at sea. As for growth in the Royal Navy, it was shown above how many ships Britain had with respect to its rivals. According to Steel’s Original and Correct List of the Royal Navy, in April 1794 the navy had 303 vessels in active service. In 1799, including captured vessels, the total had risen to 646, of which 268 had been French. By adding the 597 corsairs taken from all nations, the total number of ships taken was 942.

French difficulties

For France, whilst the army numbers were kept up by mass conscription, the French navy had no such advantage. And in addition to the problem of recruitment there were in fact three further problematic areas, namely:

– the disappearance of the Brittany crewmen. Brittany sailors had formed the core of the French navy of the Ancien Régime. With the Revolution they left en masse. Of all the navy officers in 1790, only 25% remained in 1791, the rest emigrating, occasionally even serving in the enemy navies;

– poor state of repair of the French navy, lack of investment

– the catastrophic decision by the Revolutionary government to suppress the Corps d’artillerie de la marine – it was considered too elitist. At one fell swoop, the French navy was deprived of 5,400 specialist in marine artillery.

After 1801, there were slightly fewer then 70,000 French navy prisoners in British hands. The lack of manpower and investment weighed heavily!

1797 – the year of living dangerously

1797 was a key year for British in the struggle against Revolutionary France. Faced with considerable problems at home (the mutinies of Spithead and The Nore) and invasion threats from abroad (the battles of Cape Saint Vincent and Camperdown), the navy was forced to act.

The mutinies at Spithead (April) and The Nore (May), 1797

Driven by the terrible onboard conditions, the brutal punishments and increasingly infrequent pay, the sailors of the Royal Navy mutinied twice in 1797, once in April and then again in May, first at Spithead, off Portsmouth, and then at The Nore, a sand bank off the Kent coast in the Thames where the fleet usually anchored. In fact the Spithead mutiny was an industrial dispute. And it would appear that the government was largely sympathetic, given the speed of the reparations (the difficulties were resolved in less than two months by the passing of an act of parliament), the payment of pay arrears and the pardoning of all those involved in the mutiny. On the other hand, the mutineers at The Nore were blocking the Thames, England’s supply line. Pitt reacted harshly, sending in army and other vessels favourable to the government to force a surrender – cannons were lined up on the mainland aimed at the ships in mutiny. The prime minister was also particularly sensitive regarding the mutiny because of the perceived political overtones, given the large numbers of Irish involved. The ringleader, Richard Parker, was condemned to be hanged from the yardarm 1798 – in fact (as was often the case with those thus sentenced) he jumped into the sea and drowned. But above all, the mutinies of 1797 revealed a fundamental weakness in defence. The government reacted quickly and brutally, passing the Incitement to Mutiny Act (revoked only very recently), which made any act of disaffection in the armed forces an act of treason, and thus punishable by death.

The Battle of Cape Saint Vincent, 14 February, 1797

In yet another attempt to invade Ireland, (he had made a previous try in 1796), General Hoche came up with another plan whereby an invasion would be led by the recently refitted French fleet based in from Brest together with the Batavian and Spanish fleets. The Spanish fleet was anchored at Cartagena (on the east coast of Spain), and on 5 February began the attempted linkup, passing Gibraltar and heading for Cadiz. Blown off course by strong east winds, the Spanish fleet ended up in the Atlantic, far from the port of destination but more importantly to the west of the British fleet (under Admiral Sir John Jervis) off the Cape Saint Vincent (Portugal). Commodore Nelson on board Minerve, on seeing the port of Cartagena empty and realising that the Spanish were trying to reach Cadiz, came at full speed to inform Jervis of what had happened. He too was forced off course by the winds and in fact (because of the fog and the sleepy Spanish watch) passed unnoticed through the Spanish fleet on the evening of 11 February to reach Jervis. When the winds changed, the Spanish then headed again for Cadiz. On 14 February at 8-30am, the two fleets met.

The British fleet of 15 vessels formed up in line of battle and sailed towards the Spanish fleet which, because of the winds, had become split into two groups, one of 19 and the other of 6 vessels – nearly double the number of the opposition. Before Jervis managed to stop the two parts coming back together, three of the 19 had managed to join the six. These nine vessels then tried but in vain to cut the British line in front of Jervis in Victory. As the rest of the Spanish fleet was trying desperately to join up behind Jervis’ fleet, Nelson spotted the manoeuvre and (without order) left the line of battle in order to prevent the Spanish from completing their attempt. This gave the British fleet time to group around Minerve and to engage the Spanish ships. At the end of the battle, the Spanish had lost San José and Salvador del Mundo (112 guns), San Nicolas (80 guns) and San Ysidro (74 gun), with 5,000 dead, wounded or prisoner. British losses ran to 73 dead and 227 wounded. Won by the courage and teamwork of the British admirals, not forgetting Nelson’s brilliant (if unorthodox) improvisation, this victory prevented a massive invasion of Ireland and won the blockade of Cadiz up until the summer of 1799.

The fleet of the Royal Navy

Culloden (74) Capt. Thomas Troubridge, Blenheim (98) Capt. Thomas Frederick, Prince George (98) Rear Admiral Parker, Capt. John Irwin, Orion (74) Capt. Sir James Saumarez, Colossus (74) Capt. George Murray, Irresistible (74) Capt. George Martin, Victory (100) Admiral Sir John Jervis, Capt. Robert Calder, Egmont (74) Capt. John Sutton, Goliath (74) Capt. Sir Charles Knowles, Barfleur (98) Vice Admiral William Waldegrave, Capt. Richard Dacre, Britannia (100) Vice Admiral Charles Thompson, Capt. Thomas Foley, Namur (90) Capt. James Whitshed, Captain (74) Commodore Horatio Nelson, Capt Ralph Miller, Diadem (64) Capt. George Towry, Excellent (74) Capt. Cuthbert Collingwood, Minerve (38) Capt. George Cockburn, Southampton (32) Capt. James Macnamara, Lively (32) Capt. Lord Garliesc, Niger (32) Capt. Edward Foote, Bonne Citoyenne (20) Cdr Charles Lindsay, Raven (18) Cdr William Prowse, Fox (10) Lt. John Gibson

The Spanish fleet

Santìssima Trinidad (130), Prìncipe de Asturias (112), Conde de Regla (112), San José (112), Oriente (74), Atlante (74), Soberano (74), Infante de Pelayo (74), San Ildephonso (74), San Ysidro (74), San Pablo (74), Neptuna (74), San Domingo (74), Terrible (74), Mexicano (112), Purìsima Concepción (112), Salvador del mundo (112), San Nicolas (84), Glorioso (74), Conquestada (74), Firme (74), San Genaro (74), San Francisco de Paula (74), San Antonio (74), San Fermìn (74), Bahama (74), San Juan Nepomuceno (74)

Battleship Royal Oak

The battle of Camperdown (Kamperduin), 11 October, 1797

At the end of May, 1797, the British Northe Sea fleet was so diminished (many vessels in port for repairs) that Admiral Duncan found himself blockading the port of Texel (and the whole Batavian fleet in it, under Vice-admiral de Winter) with only two ships, Venerable (74) and Adamant (50). Joined by other vessels towards the middle of June, Duncan spent the summer blockading the Texel before returning to Yarmouth on 3 October for refitting and replenishing stores. On 9 October, he received the information that the Batavian fleet had left the Texel. According to the French, de Winter was looking for the British vessels, whilst in England they said that he was attempting to link up with the French fleet with an eye to invading Ireland. Duncan left Yarmouth immediately. On arriving off the Texel on 10 October, he found 22 merchantmen but no warships. The ships which he had been blockading all summer had got away. Captain Trollope informed him that the Batavian fleet was heading south.

The two fleet were as follows:

The Batavians

Vryheid (74), Vice-admiral de Winter, Jupiter (74), Vice-admiral Reyntjes, Brutus (74), Rear-admiral Bloys van Treslong, Staten-Generaal (74), Rear-admiral Story, Cerebus (68), Jacobson, Tjerk Hiddes de Vries (68), Zegers, Gelijkheid (68), Ruysen, Haarlem (68), Wiggerts, Hercules (64), Van Rysoort, Leyden (64), Musquetier, Wassenaer (64), Holland, Alkmaar (56), Kraft, Batavier (54), Souters, Beschermer (54), Hinxt, Delft (54), Verdoorn, Mars (44), Kolff, Monnikendam (44), Lancaster, Ambucade (32), Lieutenant captain Huys Heldin (32), Lieutenant captain L’Estrille

The British

Venerable (74), Admiral Adam Duncan, Monarch (74), Vice-admiral Richard Onslow, Russel (74), Captain Henry Trollope, Montagu (74), Captain John Knight, Bedford (74), Captain sir T. Byard, Powerful (74), Captain William Drury, Triumph (74), Captain W. Essington, Belliqueux (64), Captain John Inglis, Agincourt (64), Captain J. Williamson, Lancaster (64), Captain J. Wells, Ardent (64), Captain R. Burgess, Veteran (64), Captain G. Gregory, Director (64), Captain W. Bligh, Monmouth (64), Captain J. Walker, Isis (50), Captain W. Mitchell, Adamant (50), Captain W. Hotham, Beaulieu (40), Captain F. Fayerman, Circe (28), Captain P. Halkett

Duncan sailed south south and founded the Batavians off Kamperduin (near Haarlem), on 11 October at 7am. Arriving in disorder, Duncan was forced to await the arrival of his rear. However, at 11am on seeing that the Batavians were trying to reach the land, Duncan raised the signals for each ship to ‘engage her opponent in the enemy’s line, to bear up and sail large, for the van to attack the enemy’s rear’. By accident, the British attack formation strongly resembled that of Nelson’s at Trafalgar, that is, the vessels in two parallel lines piercing the enemy’s centre and rear. The Batavian ships were arranged in two lines parallel with the coast, the frigates set back but level with the gaps in the first line.

The British ships managed to cut the Batavian line (Onslow in Monarch firstly at the rear passing between Jupiter and Haarlem and Duncan in Venerable in the centre, passing between Staten-Generaal and Vrijheid) and began to attack the Batavians from both sides. Despite the fact that the British had greater fire power, the two Batavian 74s Jupiter and Vrijheid put up fierce resistance, causing much damage to their respective opponents. Indeed Venerable was so damaged that she was forced to leave off the engagement. Even when attacked by four boats simultaneously (Triumph, Ardent, Director and Venerable – the latter coming back around to the other side), Vrijheid did not surrender until she had lost all three masts. With de Winter’s capitulation, the Batavian fleet surendered, leaving the British in possession of 11 enemy vessels – Delft sank on 14 October and Monnikendam was washed up on the beach near West Kapelle.

Even though much less experienced than the British, the Batavians fought bravely and there were large numbers of dead and wounded on both sides – 540 Batavians killed and 620 wounded, against 203 British dead and 622 wounded. Unlike the French and the Spanish who out of preference directed their cannon at the sails and masts in an attempt to limit an enemy ship’s capacity for manoeuvre, the Batavians fired at the hulls of their enemies (just like the British Navy), a fact which would explain the high numbers of fatalities and wounded and the relatively intact condition of the masts and rigging. Onlookers said that at the end of that battle the ships looked like they had never fought at all!

Conclusion

As a result of increased revenues from the colonies, huge numbers of new recruits, modernised ports, swift and summary repression of the internal problems, the relative weakness of the opposition, and victory in two key naval battles (thus preventing a full scale invasion of Ireland and also greatly weakening two enemy fleets), the British Navy both psychologically and physically laid the foundations for the crucial victories of the Nile, Copenhagen and Trafalgar.

Napoleonic navies on the web

Broadside, the personal site run by Paul Gooddy

http://www.nelsonsnavy.co.uk

HMS Victory, virtual tour

http://www.stvincent.ac.uk/1797/Victory/index.html

The letters and despatches of Horatio Nelson (War Times Journal) http://www.wtj.com/archives/nelson/

The National Maritime Museum (UK)

http://www.nmm.ac.uk/

Royal Naval Museum, Portsmouth (UK)

http://www.royalnavalmuseum.org/

Musée de la marine (Fr)

The site (still partially under construction) of the French Naval Museum (in French)

http://www.musee-marine.fr/

British Naval Chronology, 1793 to 1803

18 December 1793, Toulon, failed attempt to the capture and destroy the French fleet by Lord Hood and Sir William Sidney Smith (54 vessels and 120 cannon were rescued by the French)

1 June 1794, the ‘Glorious First of June’, sea battle in the Atlantic 150 leagues off the Ile de Ouessant. Even though the convoy of grain guarded by the French warships reached port, the French lost 33 ships of the line, 7,524 men, against 290 dead and 858 wounded on the English side

5 February, 1794, British capture of Martinique

19 February, 1794, British capture of San Fiorenzo, Corsica, by Lord Hood

beginning April, 1794, capitulation of Bastia, Corsica, to Lord Hood

mid August, 1794, capitulation of Calvi, Corsica. Corsica was under British control until 1796 when it was returned to France

20 March, 1794, British capture of Guadeloupe (retaken by France, end of 1794)

April 1794, British capture of Tobago and Santa-Lucia (Santa-Lucia retaken by the French, summer, 1795, taken back by the British, April 1796)

1795, French attempt to retake Corsica beatne off by the British Mediterranean fleet under Admiral Hotham – loss of the ships of the line Censeur and Ça-Ira on the French side and the ship of the line Illustrious, on the British side

23 June, 1795, action at Ile de Groix – French loss of 3 vessels (Tigre, Alexandre, and Formidable)

July 1795, Nelson took Elba

27 June, 1796, British evacuation of Livorno

17 August, 1796, the Batavian expedition to take the Cape of Good Hope beaten back by Vice-admiral Sir Keith Elphinstone. The Batavians lost 9 ships

19 October, 1796, recapture of Corsica by the French and subsequent British loss of control in the Mediterranean

December 1796, British evacuation of Elba

December 1796, failed invasion of Ireland

February 1797, British capture of Trinidad from Spain

14 February, 1797, defeat of the Spanish fleet at the Battle of Cape Saint Vincent at the hands of the Royal Navy. Spanish losses: 14 ships, including two 112s, one 80 and one 74, 5,000 dead, wounded and taken prisoner; British losses: 73 dead, 227 wounded, 5 ships very seriously damaged

April and May, 1797, mutinies at Spithead and The Nore in England

24-25 July, 1797, action in Tenerife – British attempt to seize a ship laden with silver anchored in the port. British disaster against 8,000 Spanish and 100 French soldiers. British losses: Nelson lost his right arm, 102 men drowned, 45 killed, 5 lost, 105 wounded.

11 October, 1797, Batavian defeat at the Battle of Camperdown at the hands of the British navy. Batavian losses: 11 ships of the line, 540 dead, 620 wounded; British losses: 203 dead, 622 wounded

1 August, 1798, French defeat at the Battle of the Nile at the hands of the British navy. French losses: 11 ships of the line, 2 frigates, 1,700 dead, 1,500 wounded, 2,000 taken prisoner (all set free on land); British losses: 218 dead, 678 wounded (including Nelson in the head)

September 1798, yet another failed French invasion of Ireland. French losses; 7 vessels, 425 dead/wounded, 1,870 prisoners; British losses: 13 dead, 75 wounded

April 1799, Admiral comte de Bruix slipped through the blockade and attempted to join the Spanish fleet in Cadiz – seeing Lord Keith blockading of Cadiz, he avoided battle and entered the Mediterranean. Bruix finally managed to join up with the Spanish fleet on 22 June at Cartagena. The allied fleets of France and Spain then again gave British vessels the slip and, hotly pursued by them, managed to reach Brest, 13 August, 1799

May 1799, Sir Sidney Smith shelled Bonaparte outside Saint John d’Acer, forcing him to lift the siege

March 1800, British blockade off Genoa, where Masséna was besieged by the Austrians under the general von Ott

September 1800, French capitulation of Malta to the British fleet which had been blockading the island for two years

2 April, 1801, Battle of Copenhagen, British victory. Danish losses: 480 dead, 570 wounded, 2,000 prisoners/lost in action (all prisoners were returned before 12 April); British losses: 256 dead, 688 wounded.

6-12 July, 1801, action at Algeciras between French/Spanish vessels and British ships. British losses: one ship of the line (Hannibal) 130 dead, 240 wounded; French/Spanish losses: 5 ships of the line, at least 1,700 dead

A rare gold Spanish colonial coin, with documented provenance to the famed 1715 Plate Fleet wreck, highlights Daniel Frank Sedwick LLC’s Treasure Auction 28 on Nov. 17.

The 1713-MXO J coin is a Royal gold 8-escudo coin, a coin literally “fit for a king,” that was recovered in 1998 from a sunken Spanish treasure fleet. The coin, only the second known of the year, is graded by Numismatic Guaranty Corp. as Mint State 66 and is the only example of its date slabbed by any third-party grading company.

The auction firm estimates the coin to realize $300,000 and up.

“This coin is the pinnacle of Spanish colonial numismatics,” said Daniel Sedwick, president and founder of the company. “As a Royal 8 escudos, it is a coin so large, beautiful, and perfect as to be considered among the most desirable gold coins in the world — both then and now. It represents the finest in colonial minting abilities at the time. Plus, when you consider this specimen’s documented discovery on one of the most famous shipwreck sites ever, you realize just how truly special and rare this coin is. We’ve sold hundreds of gold cobs from the 1715 Fleet but this is the first time in 14 years of auctions that we’re offering a 8 escudos Royal.”

From a documented wreck

Ben Costello, president of the 1715 Fleet Society, called the coin a superb specimen with a securely documented provenance to the Corrigan’s wreck site of the 1715 Fleet. The site is named after Hugh Corrigan, described as a beachcomber who began finding coins on beaches near Vero Beach in the 1950s.

“Fleet collectors are delighted by the first time offering of this gorgeous and very rare 1713 8 escudos Royal,” said Costello, in a press release from the firm. “Only two examples are known. This piece is surely among the best, if not the best, of the entire 1711 to 1713 series of cross-with-crosslets Royals.”

The specially struck presentation piece was minted in 1713 at the Mexico City Mint and bears the OXM Mint mark to the left of the shield. Below the Mint mark, the initial J stands for assayer José de León, the mint official responsible for the entire coinage production. The assayer’s mark was added so that if any coins were made of suspect quality, the monarch could punish the one who cheated the crown.

The Royal shield and crown at the center represent King Philip V’s authority over Spain and her colonies. To the right of the shield is a vertical VIII representing the denomination of 8 escudos. The legend reads PHILIPPVS V DEI G 1713 with florets in the spaces between words. The DEI G stands for Dei Gratia, “by the grace of God.”

On the reverse, a framed cross is in the center with stylized fleurs-de-lis in the quadrants. The legend there is HISPANIARVM ET INDIARVM REX (“King of Spain and the Indies”) with florets in the spaces between the words and a smaller cross at the top.

What is a Royal?

What sets a Royal, also known by the Spanish term galano, apart from the regular cob issues is its detailed, careful striking on a specially prepared, round planchet of uniform thickness and weight.

The regular cob coinage was quickly produced in quantity by hammering irregularly shaped planchets. Often, whole portions of the design were weakly struck or missing entirely. This is not the case with Royals.

From start to finish, the production of a Royal was a careful, thoughtful process.

The dies were specially prepared, with design elements accurately punched to maximize detail.

The gold planchet used was of full weight and in a uniform, round shape to fit all of the design. Finally, a mint worker would strike the planchet with the hammer die, exerting uniform, strong pressure — a very difficult task.

Afterward, a gold Royal would be handled separately, not transported in large sacks or casks with regular coins. By intention, very few cob 8-escudo Royals were minted, due to the time and resources it took to make them.

After being struck at the mint, this 8-escudo Royal departed the New World aboard a Spanish galleon in the 1715 Plate Fleet. Its destination was mainland Spain, where it would have been given or awarded to an important Spanish official, a member of the Royal family, or the king of Spain himself may have been an intended recipient.

A fleet filled with treasure

In addition to several other Royals (the 1715 Fleet is the primary source for gold 8-escudo Royals), the ships carried a wealth of treasure: silver and gold coins from the colonial mints, fine jewelry and religious objects, precious gemstones, spices, and Kangxi china from the Manila trade route. Large quantities of contraband, too, were smuggled onto the ships, bypassing the tax that was to be levied to the king.

Much of the official treasure onboard was intended to refill Spain’s coffers. The kingdom’s finances were in disarray following the misrule of King Charles II and the subsequent War of Spanish Succession. Spain was reliant on the annual voyages from the New World to bring wealth to the mainland. The war and its political instability had delayed the fleets, and large quantities of treasure had piled up in Mexico and Colombia. The fleet, carrying enormous amounts of treasure from an entire continent, was needed in Spain soon.

The fleet combined two fleets, the Tierra Firma Fleet, from Cartagena, loaded with Peruvian and Colombian treasures, and the New Spain Fleet, from Mexico, with coins, gemstones, and china. The combined flotilla comprised 11 Spanish vessels, with a single French vessel, the Griffon, tagging along. On July 24, 1715, they departed Havana, Cuba, on a north-northeasterly course to sail along the east coast of Florida before crossing the Atlantic and onwards to Spain.

Having initially left under fine sailing conditions, the fleet soon encountered violent weather and, by July 30, entered the path of a hurricane. In the early hours of July 31, just off Florida’s coast, between what is now Cape Canaveral and Fort Pierce, the 11 Spanish ships were cast upon shoals by the waves and destroyed.

Close to 1,500 sailors and officers were killed. The treasure cargo was scattered across the ocean floor as the ships broke apart. Survivors who made it ashore were spread along the coast for miles. Only the French vessel Griffon made it through the storm and continued on to France, unaware of the Fleet’s complete annihilation.

Survivors, led by Adm. Don Francisco Salmón, set up camp and sent a small party to Cuba to deliver news of the tragedy and launch a rescue mission.

Spanish authorities in Cuba dispatched several ships to supply the survivors and begin salvaging the sunken treasure.

For months, the Spaniards worked the waters off the coast, recovering millions of coins and a good amount of other artifacts. Pirates who learned of the Fleet’s destruction harassed the Spanish salvors and made off with some of the treasure.

By 1718, the Spanish considered their salvage operation a success and departed the area. Even so, significant amounts of treasure remained just off Florida’s shore, buried in the sand and trapped beneath debris. For almost 250 years, the coins and artifacts would remain lost — among them this 1713 Royal 8-escudo coin.

Modern treasure hunt

By the 1960s, advances in diving technology and metal detecting allowed determined seekers the chance to find Spanish colonial coins from the Fleet along the beaches between Melbourne and Stuart (an area now called the Treasure Coast).

Retired building contractor Kip Wagner and the Real Eight Co. organized salvage operations on what eventually became eight known wreck sites of the 1715 Fleet (at least three of the ships have yet to be located). In conjunction with the state of Florida’s lease system, the salvors were able to recover large quantities of shipwreck silver and gold coins in addition to artifacts and jewelry.

Royal Battleship Kit

This 1713 Royal 8 escudos now being offered was recovered on Aug. 16, 1998, by diver Clyde Kuntz. Kuntz, operating from the salvage vessel Bookmaker captained by Greg Bounds, was diving on the Corrigan’s wreck site just north of Vero Beach.

The site, then leased by the Mel Fisher company, is named for Hugh Corrigan who owned a house on the beach there.

On that day, Kuntz was searching several holes in the ocean floor. Around the third hole, he pulled a gold cob 8-escudo Royal dated 1698 (a coin that, to this day, is unique) from a crack in the hard pan.

He stored it in his face mask to ensure he didn’t lose the valuable find. He returned to the salvage vessel to much elation among the crew for the impressive find.

Upon returning to the water, he searched another hole and located the gold cob 8-

escudo Royal now being offered. This time, he kept the coin in his diving glove so it could not be lost again. The discovery of two cob 8-escudo Royals in one day attracted much attention, and the covers of several salvage publications featured both coins.

According to Treasure Quest magazine’s November-December 1998 issue, after finding the second Royal, “It was time to call Mel Fisher in Key West on Greg’s cellular phone. Mel was in his office and when he heard the news he gleamed. ‘Congratulations! Now go find some more!’ ”

At the time, the pair of Royals was estimated to be worth $150,000, or half as much as the single example is expected to realize, at a minimum, today.

After the finding, this 1713 Royal was documented and tagged in accordance with the state of Florida’s treasure hunting laws.

The state, using a point-based system, receives 20 percent of each year’s finds and first choice among the items recovered. Upon the division, this coin was returned to the salvors for private sale. It spent many years off the market, residing in the numismatic cabinet of numismatist Isaac Rudman.

According to Connor Falk of the Daniel Frank Sedwick firm, “We cannot reveal the identity of the consignor for this coin. It was at one point owned by Isaac Rudman, but that’s all that can be said.”

The coin is “the closest to perfection that Spanish colonial cob coinage could ever achieve,” according to the auction house.

Gold, famously, is not affected by the corrosive salt water that eats away at silver coins typically recovered from shipwreck sites.

Connect with Coin World:

Sign up for our free eNewsletter

Access our Dealer Directory

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter